7.89 miles 4h 30m ascent 151m

Edenbridge-Edenhall (5.8 miles on the Eden Way)

This walk was mostly over fields or through woodland but with some road walking. There were more gates than stiles, what quagmire we found was manageable and we had only one navigation error (my own). We crossed bridges both old and new, of stone, of wood and of metal. There were herons and ducks, megaliths and pebbles, artworks and industry, sculpture and excavation, railways and viaducts, waterfalls and magnetostriction, memorials and memories. We ate our lunch in comfort, and walked with Long Meg’s daughters. Not a bad day.

In this section we took the Eden Way down to Langwathby, then crossed the river and followed the Ladies’ Walk to the next Eden Benchmark.

Shaggy Inkcap

These impressive mushrooms, Shaggy Inkcaps, were growing in the grass by the Cypher Piece Eden Benchmark. I took a second look at the sculpture and this time had a closer look at the inscriptions on it: a fish, a date in Roman numerals (21 12 1996), and various other carvings that I hadn’t noticed on the previous visit.

Stepping Stones

Poetry stones

Poetry Stones

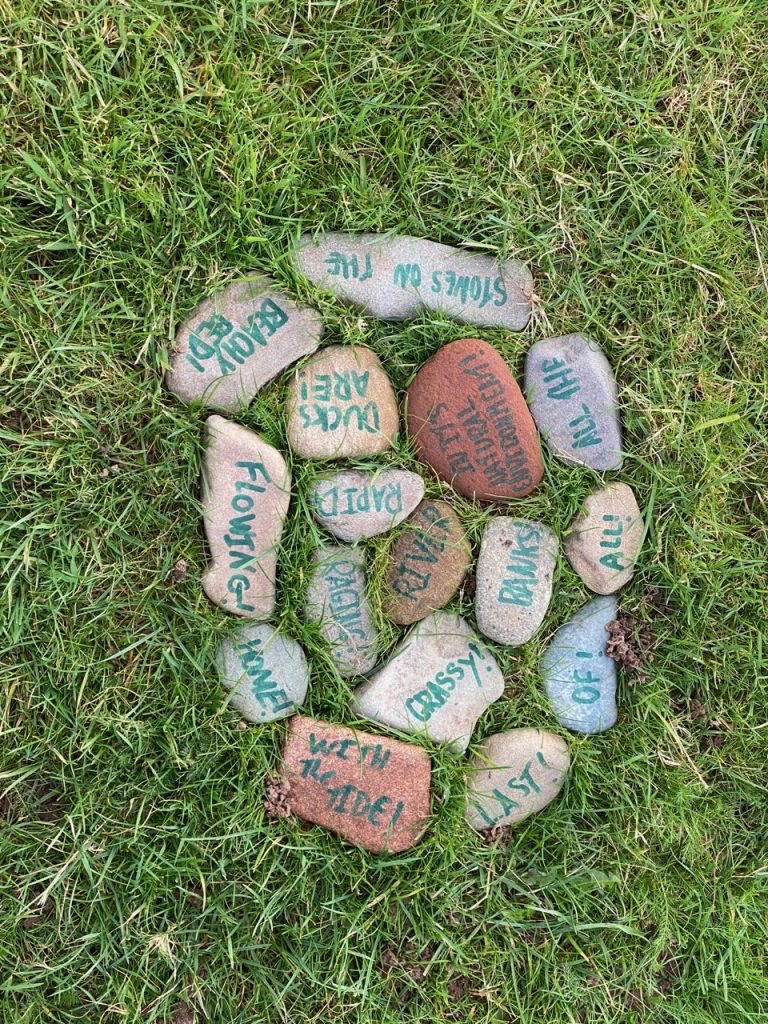

Our first challenge was after crossing Edenbridge and getting the dogs over the stile onto the riverbank. A water-filled ditch blocked our path. In drier times it would have been a doddle and in wetter times a challenge but we were lucky. The river was not running particularly high and where the ditch’s water met the river we found lines of stepping stones. I’m pretty sure they were there by human design rather than chance. Stones inscribed with a word or phrase had also been laid by the river bank in groups and some arranged as poems.

Swinging seat

River Eden

Swinging Seat

We had easy walking in the fields beside the River Eden, with beautiful views of Kirkoswald’s Belltower and the river itself. The Eden Way guidebook talks of swing seats along this part of the river. The stick on a rope, seen with Christy in the photograph above, isn’t what I was expecting. The real swinging benches were a little further along but it was too soon in the walk to stop and swing.

We joined the Kirkoswald to Glassonby road at Daleraven Bridge, to cross Glassonby Beck. A finger post after the bridge showed the way to the public footpath. We followed a short, steep path up to a stile but then I had my navigational faux pas. I thought we should have been closer to the river bank went back down to a lower, slightly less obvious, and overgrown path. A voice in my ear suggested this was the wrong way but I paid insufficient heed. The path grew less obvious, more overgrown and, eventually, gave up all pretence of being a path. Back to the stile we went.

Bad walkway

Good walkway

The new, correct, route wasn’t a walk in the park though and included a long section of quagmire crossed by planks, some had rotted, some had fallen into the mud, some had adopted a jaunty angle and some pivoted unexpectedly. We knew the quagmire exceeded boot depth by the depth Christy’s legs sank into it. God knows how the dachshund made it through. Belly surfing?

The rotted plank-way brought us to a stile erected in the mud but, luckily, a gap in the fence meant we didn’t need to lift the muddy dogs. We were now in Tib Wood with its better quality wooden walkway. Its cross beams were thicker than needed and I wonder if they might be ‘retired’ railway sleepers. The walkway took us over several wee ditches and kept us out of the mud. Some sleepers were missing but the support beams underneath were wide enough for us. It might be trickier in wet weather.

Lacy’s Caves

The guidebook says to look out for an unmarked path to Lacy’s Caves. It was to be found after passing two sandstone walls and a steep incline in the path but was supposedly hidden by a fallen tree. We found a sandstone wall covered with carved graffiti and there was a path leading downwards, but we kept to the main path which climbed then turned by a second sandstone cliff. The fallen tree has gone, but there is a sign for Lacy’s Caves and the path is obvious.

Samuel Lacy, who lived in Salkeld Hall in the 1790’s and Lieutenant-Colonel of the Cumberland Militia, had the caves excavated. Why is uncertain but the building of follies was fashionable at the time and he may have wanted something similar to the caves at Wetheral. He had ornamental gardens planted nearby and entertained guests in caves, though at one time he actually hired a hermit to live in them. More about the Colonel later.

Long Meg Mineworks

Not far from the caves were the remains of Long Meg Mine. The footpath runs beside the mineworks for quite a way. The brick parts look like a bomb-site, but the concrete sections have a “Chernobyl” vibe to them. I was almost surprised that the “Private Land – Keep Out” signs were in Roman rather than Cyrillic script. The mine closed in 1976 having operated for over a century. Originally a gypsum mine, its main output later switched to anhydrite used in the production of sulphuric acid and fertilisers. The mine once had its own narrow-gauge railway line and had its own steam locomotives.

There was a railway viaduct over to our right, but the trees frustrated my attempts to photograph it, as they did at the Force Mill waterfalls. We left the woodland walk for a lane at an electricity substation and by the path was this T11, which I couldn’t help comparing with the T101 and T1000 (Terminator models)

It can’t be reasoned with, it can’t be bargained with. It doesn’t feel pity or remorse or fear. And it absolutely will not stop. Ever.

Failing Keystone

A number of dilapidated buildings here are likely further remnants of the mine. The guidebook mentions a “Ceramic Pavement” an artwork representing the River Eden between Armathwaite and Culgaith. It is still here but a little worse for wear, which is a real shame.

I found a photograph from 13 years ago on geographic.co.uk and it looks as though some parts of the artwork are missing or perhaps overgrown. That photograph shows a section explaining the piece: “Made by schoolchildren of High Hesket, Armathwaite, Langwathby and Culgaith with the help of Michael Eden. With thanks for the support of Hanson Bricks and Glassonby Lodge”.

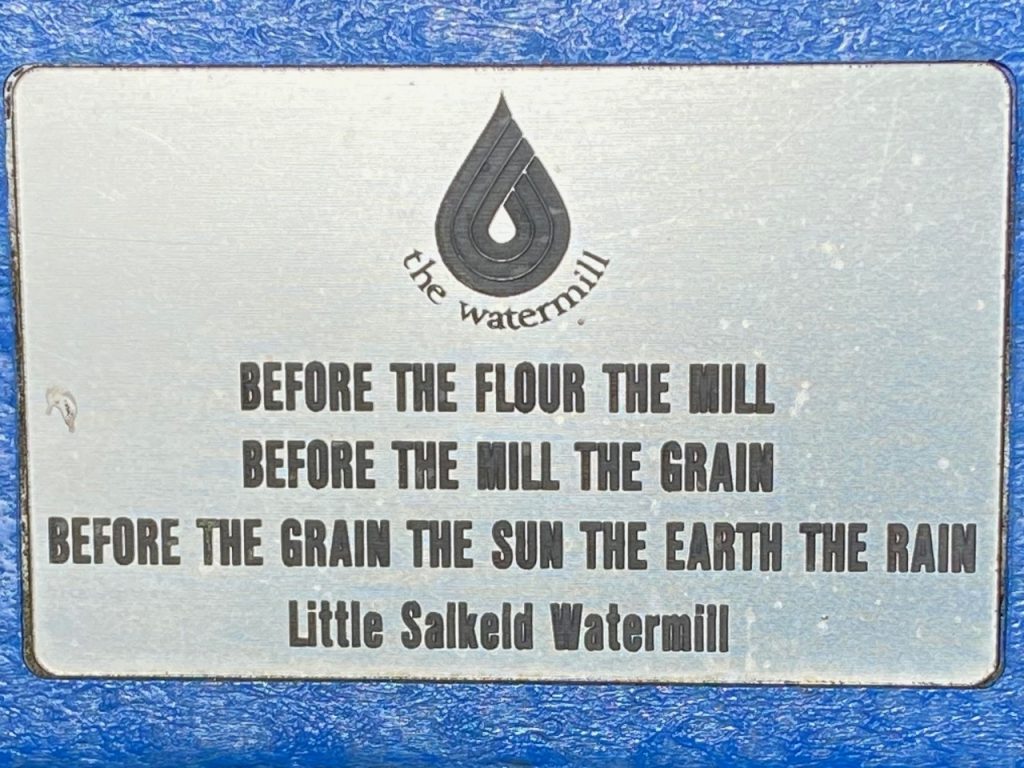

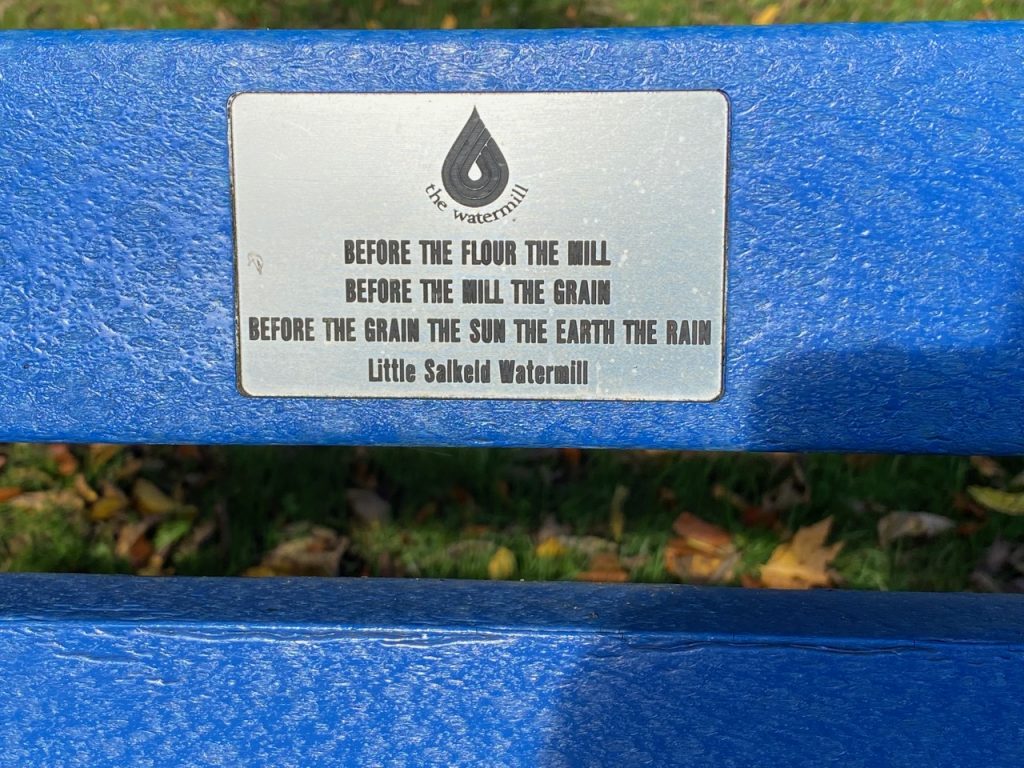

We also saw a wooden post that presumably once held ceramic tiles similar to those we saw on earlier Eden Way walks. The tiles are gone but another geograph.co.uk photo from 13 years ago shows it with a ceramic tile of Housemartins. Little Salkeld was a short walk away and its village green was perfect for lunch. We got a bench each. And while we sat, Christy, who cannot abide stopping, collected twigs and leaves to throw at my feet, while Mabel rested on Audrey’s lap. It was only when we were getting ready to start walking again that I noticed the small plaque on my bench…

The mill itself was a couple of minutes walk away and we passed by it as we left the village. It is difficult to miss being painted a bright pink. There has been a mill here since the fifteenth century but the present mill dates from 1745. (Now there’s a date with some history!) It is the last active water-powered flour mill in Cumbria.

These small mills lost out when large quantities of imported wheat began to arrive at west coast ports where much larger mills were built, such as those at Silloth.

Easy Rider

St Peter’s Langwathby

Little Salkeld to Langwathby is a country road with little to see other than farmland and the nearby railway. We could have been in autopilot were it not for the cars, the road being busier than our previous walks. We noticed someone in a Hi-Vis vest standing by the road up ahead gave us something to think about. We were quite close before I realised it was dummy astride the bicycle. And why there was sign reading “Easy Rider” I don’t know. (Edit: I do now: The Sustrans C2C route comes along here). But the Easy Rider sign did prompt a Proustian memory for me. I was given a box of cassettes as a child – as was often the case these were of varying genres and not specifically chosen for me – varied books (second hand) often came in boxes like this too. Perhaps these moulded my eclectic tastes, or left me yearning for a treasure that is only found by chance. In such musing I passed the time to Langwathby.

Only when I saw the road sign for Langwathby was I brought back to earth, wondering what a “wath” could be. I knew I had heard the term before but couldn’t think where. ‘Lang’ (long) and ‘by’ (village) were easy enough. Well, the waths I had heard before were the Solway Waths. Old Norse for Ford. Oh, and specially for my Cumbrian companion, locals pronounce it Langanby according to t’internet.

Langwathby bridge

Apples Galore

Langwathby has a large village green with a pub standing but the ground is so uneven that cricket would be a challenge. But it has something you don’t often see on village greens. Goalposts.

Eden Way turns left onto the A686, a very busy road but furnished with a pavement. But we turned right. We strayed from the Way to reach the next Eden Benchmark Sculpture, on the other side of the river. So to Langwathy Bridge. Built as a temporary measure in 1968 after the original 1686 bridge was washed away it is now in the Guinness book of Records as the country’s longest-lasting temporary bridge. I does at least have a pedestrian walkway so we didn’t have to traffic.

The apples in the photograph above covered our path to the bridge. The dogs, who would normally snap up any apple at home, just ignored these.

South Rising

There is a path along the western bank of the river, the Ladies’ Walk, which was originally made for the Musgrave Ladies of Edenhall, This took us along the edges of fields and through riverside woodland. There were even sets of stone steps where needed and benches where a lady might tarry to admire the river.

The next Eden Benchmark sculpture was a little under a mile away, directly on the path. ‘South Rising’ by Vivian Mousdell is two large pieces of Lazonby sandstone. The artwork “pays tribute to a vigorous ecosystem, representing the river’s perpetual journey and the annually recurring movements of migrating fish and birds. The horizontal stone alludes to the river itself, flowing north, and the tall vertical stone, with perhaps a passing resemblance to Long Meg, inclines south toward the rivers distant source. Chiselled with a surface texture reminiscent of water reflected sunlight, both stones have been carved in sweeping curves like the surrounding landscape, creating a rhythmic energy passing from one to the other.“

The impression I had was of a split nutshell. We did stop a while and that’s what matters I suppose. The Ladies’ walk took us about a third of a mile further along the river then back to Edenhall passing a couple of hundred metres from St Cuthbert’s Church. We had seen several memorial plaques on the riverside benches but here there is a memorial stone beside a tree with the inscription “Planted in loving memory of Michael William Benn 1970-2007”. I am pleased to say that the tree is thriving.

A little further on we came to the first of Edenhall’s two crosses. This is the older cross, but not as old as I had thought. I presumed it was Norman, and an ancient cross may once have stood on the steps here. The plinth actually dates from the fifteenth century but the present cross wasn’t present in 1840 when it was recorded that “in the lane leading from the vicarage house to the church are some stone steps which appear to have been surmounted by a cross“. So it was probably placed here in the later nineteenth century.

Edenhall Cross

War Memorial

The other cross is the WW1 war memorial which I would confidently say is early twentieth century. Inscribed on its plinth is “We lie dead in foreign lands, that you may live here in peace.” It is peaceful now.

We passed a house covered with impressive Victoria creeper and as we stood admiring it a local told us we had missed its most impressive show by a week.

Victoria creeper

No visit to this area would be complete without a visit to Long Meg and her Daughters. And I will have to say I was impressed. On arriving I thought there were two circles because there were stones either side of the road. But the circle is so big the road runs through it. I’ll let you read Wordsworth’s description before I say any more.

A weight of Awe not easy to be borne

The Monument, William Wordsworth 1822

Fell suddenly upon my spirit, cast

From the dread bosom of the unknown past,

When first I saw that family forlorn;

Speak Thou, whose massy strength and stature scorn

The power of years – pre-eminent, and placed

Apart, to overlook the circle vast.

Speak Giant-mother! tell it to the Morn,

While she dispels the cumbrous shades of night;

Let the Moon hear, emerging from a cloud,

At whose behest uprose on British ground

That Sisterhood in hieroglyphic round

Forth-shadowing, some have deemed the infinite

The inviolable God that tames the proud.

The circle is thought to date from 1500 BC. There are 59 (or possibly 69) stones in a circle 109m across. Long Meg is the tallest, a 3.6m monolith of local sandstone standing 25m outside the circle and aligned with the centre of the circle at midwinter sunset. Her Daughters are mostly granite glacial erratics but four, specifically placed to mark calendar events, are quartz. We found fresh yellow roses laid on some of the stones.

You really can’t appreciate the circle from these photos I’m afraid. Legend says you can’t count the stones without going mad or losing count, but if you do count them the same twice you will call down very bad luck. Colonel Lacy, he of the caves, tried to blow the stones up to make the land more useful but his men were frightened away by a sudden thunderstorm that they interpreted as Long Meg showing her displeasurea.

Long Meg and her daughters