A castle (that’s not a castle), on an island (that’s not an island).

National Trust

DRAFT STILL BEING WRITTEN

6.01 miles 4h 2m ascent 64m

Holy Island is an island, for 12 hours of each day. A pilgrims’ route across the sands is marked by tall poles and was the only access, other than boat, until the modern causeway was built in 1954. Apparently, before that, local taxi drivers would happily drive across the sands.

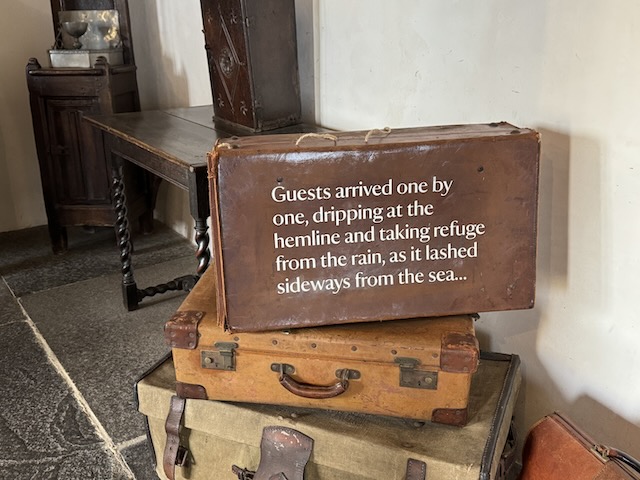

We checked the tide times and drove across half an hour or so into a “safe crossing period”. I’m pleased we weren’t walking because the road is narrow and the ground beside it either under standing water or very waterlogged. The small parking bays along the route were still submerged.

There is a large car park near where the causeway joins the island and several signs asking folk to park there rather than in the village. Contactless pay-and-display. Our route was straightforward: around the island on the coastal path, strike out for the north coast if we could see a way and explore the castle and village towards the end. There was light rain when we set out and though the temperature was above freezing, we were walking into a 35 mph north wind. The rain bit into our faces like hail and the “feels-like” temperature was -5°C. I wished I had brought winter rather than autumn gear.

Causeway, Coastal path, bitterly cold wind, rain painful on our faces.

At least the ground wasn’t too wet. The first section, heading north, was over scrub land with cows grazing here and there. It is obviously well walked and the route obvious. I don’t have many photos from there because my phone was tucked away from the rain.

A number of faint tracks led northwards into the dunes but we decided against turning into the wind again. The wind would be a constant companion throughout the walk but the rain stopped and patches of blue sky appeared. The sun broke through.

A triangular object to the north caught my eye. It looked like the steeple of a Scandinavian church. We decided to head up onto the dunes for a better view and eventually made our way to it.

What we found was a 10m tall pyramid. This is a Daymark, an old navigation aid for shipping, standing on Emmanuel Point. It was built between 1801 and 1810 by Trinity House and is one of the earliest Daymarks built in Britain (possibly the earliest one).

The waves crashing against the coast were an impressive sight with spumes (is that a word?) of white water jumping up when huge waves collided. But there is obviously some law of nature that prevents such things happening while I try to catch it on video.

We turned our back to the wind, which made a considerable difference and headed back of the coastal path which took us past a bird hide and several birds of wire or willow. I asked Audrey if those with a forked tail were swifts, swallows or house-martins but she couldn’t help me. I didn’t consider sand martins. My money is on swift.

Our initial view of Lindisfarne Castle was a silhouette, distant, atmospheric, devoid of colour. The photograph at the beginning of the post. as we approached now, it was intermittently bathed in sunshine. Once we could make out details the castle struck me as looking Spanish or perhaps French, definitely not a classically English or Scottish castle look. And as we came closer it looked stranger still with features reminiscent of Tudor houses. I knew nothing of the castle at that time so found the history given on information boards quite interesting.

The Castle was built about 1550 on the order of Henry VIII. It was strategically important in the Anglo-Scottish wars and saw action in both the English Civil war and the Jacobite rebellion. It remained garrisoned until 1893 after which it fell into disrepair but was rescued by Edward Hudson who bought it in 1901. He engaged the architect Edward Lutyens for the renovation.

“The result was an Edwardian country mansion set largely within the structure of the old fort. It comprised four public rooms, nine bedrooms, and a bathroom (a second bathroom was added later). Most of those who visited loved Lindisfarne Castle, including Lutyens and his children. Others were less enamoured, including the Prince of Wales (the future George V), and Lutyens’ wife Emily, who liked neither Hudson nor what she saw as his cold, smoky castle. Another visitor, the author Lytton Strachey, was obviously a city boy at heart, and found the castle uncomfortable and far from his taste.”

Hudson never married and had intended passing Lindisfarne to the son of a friend when he died but that chap was killed in the war. [Correction: Hudson married Ellen Woolrich when he was in his 70s]. Hudson sold the castle and one of its subsequent owners passed it into the care of the National Trust in 1944. I can’t help being surprised that the National Trust was active in the midst of WW2. But the castle one visits today is the National Trust’s recreation of the Hudson/Lutyens version.

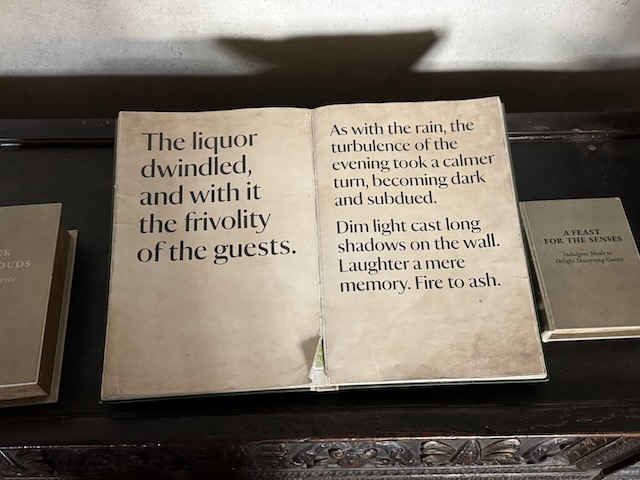

I’m not really sure how to describe the inside of the castle. The rooms wouldn’t have been out of place in “Myst”. Each is like a page from one of those “search and find” books so popular in the 1980s. There is even an I-spy trail, aimed I am sure at children, but who can resist walking round a room trying to find a pipe, a book, a ship… I couldn’t find the phoenix, unless phoenix is another name for fireplace bellows. The National Trust have some nice pictures of the rooms.

And just in case all this wasn’t enough, there was also an immersive light and sound installation, ‘Embodied Cacophonies’ by Liz Gre. It is best I not comment further lest I come across as a philistine. Oh, sod it, they could have done with losing the storage heater.

Outside the castle there are the Lime Kilns, which we glanced at from afar, and “The sheds”, made from upturned herring busses (boats), also part of the original Lutyens plan. There are three of these sheds by the castle and more near the harbour. These were, apparently, the inspiration for the shape of the Scottish Parliament building.

Gertrude Jekyll, “Bumps” to Edward Lutyens, created over 400 gardens in her time, was a regular visitor and designed what is now the Gertrude Jekyll Garden beside the castle. We sat in the garden very briefly but it was too cold and windy to stay. I didn’t take any photos. Summer photographs show it better. The NT restored Jekyll’s original planting plan in 2003 but it is past its best this late in the year.

I was intrigued by Jekyll, perhaps because of her surname. Robert Louis Stevenson was a family friend borrowed her surname for Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. At that time the name rhymed with Seek-All and the title was a play on the Victorian’s name for hide and seek, hide and seek-all. Apparently the modern Jek-ill pronunciation is a 1940s Hollywood development.

I googled the great lady, expecting tales of an elegant socialite but found photos showing someone I would expect to call me “Young Man”, despite my grey hair. But she seems to have been quite a very accomplished woman: author, artist, landscape and garden designer, embroiderer, blacksmith. And it was she who influenced Lutyens rather than the other way round.

“A garden is a grand teacher. It teaches patience and careful watchfulness; it teaches industry and thrift; above all it teaches entire trust.”

Gertrude Jekyll

From Gertrude’s garden we headed along to the harbour. A line of benches gave us somewhere to sit while we went “full-British”, coats fastened up tight, eating sandwiches and drinking from a thermos, looking at Bamburgh castle across the bay and marvelling at the waves.

The harbour had more of the herring busses, used as sheds and a great many lobster pots, all looking quite new. Our next stop was the Heugh (p. Hee-uff), a short rocky ridge with the foundations of an Anglo-Saxon church, remains of the Lantern Chapel, a shipping beacon, a war memorial Lutyens designed by Lutyens and a coastguard observation tower converted into a public viewing point.

The Heugh does offer good views, the castle standing proud like a mini Mont-Saint-Michel, the ruins of St Osborn’s fort, Bamburgh Castle and the Farne Islands across the water beyond Guile point, the priory ruins with their rather unusual statue of St Cuthbert and the tiny St Cuthbert’s Island (otherwise known as Hobthrush). Cuthbert is said to have lived their when he wished to escape the other monks and as a prelude to his move to the Farne Islands.

For some reason the Priory and its museum were so we had to explore from the outside.

King Oswald (St Oswald) gifted Lindisfarne to the monks of Iona who sent St Aidan to establish a monastery here in 635AD.

Sometime in the 670s a monk named Cuthbert joined the monastery at Lindisfarne. He eventually became Lindisfarne’s greatest monk-bishop, and the most important saint in northern England in the Middle Ages.

As prior of Lindisfarne, Cuthbert reformed the monks’ way of life to conform to the religious practices of Rome rather than Ireland. This caused bitterness, and he decided to retire and live as a hermit. He lived at first on an island (now called St Cuthbert’s Isle) just offshore, but later moved across the sea to the more remote island of Inner Farne.

On the insistence of the king, however, Cuthbert was made a bishop in 685. His new duties brought him back into the world of kings and nobles, but he acquired a considerable reputation as a pastor, seer and healer.

English heritage

I feel a connection with St Cuthbert. I was in St Cuthbert’s House at school and would live on a road named for him. He had a recognisable “saintly” life. Born in a well to do family, he became a warrior and fought in at least one battle. but his life changed on August 31st 651AD. He saw a light descending from heaven then return escorting a soul. That was the day St Aidan, died on Lindisfarne. Cuthbert went to the monastery at Melrose, also founded by Aidan, and asked to be admitted as a Novice.

“St Cuthbert was called to be a hermit on Lindisfarne. This was more than a thousand years ago. There were only small wooden huts there then, and the wind and the wild sea and everything that lived in the wild sea. Cuthbert went out there to the monastery, but the monastery was not far enough and he was called out further. He rowed to an empty island, where he ate onions and the eggs of seabirds and stood in the sea and prayed while sea otters played around his ankles. He lived there alone for years, but then he was called back. The King of Northumbria came to him with some churchmen, and they told him he had been elected Bishop of Lindisfarne and they asked him to come back and serve.

There’s a Victorian painting of the king and the hermit. Cuthbert wears a dirty brown robe and has one calloused hand on a spade. The king is offering him a bishop’s crosier. Behind him, monks kneel on the sands and pray he will accept it. Behind them are the beached sailboats that brought them to the island. The air is filled with swallows. Cuthbert’s head is turned away from the king, he looks down at the ground and his left hand is held up in a gesture of refusal. But he didn’t refuse, in the end. He didn’t refuse the call. He went back.Paul Kingsnorth, Beast

After his death a Cult of Cuthbert gradually formed. His body remained “uncorrupted” for years after his death and his shrine became associated with numerous miracles. Lindisfarne became a major pilgrimage centre and became wealthy. Cuthbert’s body was removed in 870AD to protect the holy relic from despoilment in the ongoing Viking raids. Wherever the body rested, more miracles occurred. He was eventually buried in Durham, where the cathedral now stands.

The monks returned from Durham in the 11th century, fleeing William the Conqueror’s ‘Harrying of the North’, and the priory ruins are date from that time. The monastery was dissolved by Henry VIII but the buildings remained in use as a military base until the castle was complete. They were ruins by the late eighteenth century.