5 miles 3h 4m ascent 432m

Signalhøjden, Narsarsuaq, Greenland

Breakfast: scrambled eggs, crispy bacon and mushrooms. View: an iceberg strewn fjord, on one side Erik the Red had established a Norse outpost in 986 AD, on the other, the US built airstrip at Narsarsuaq. A small aeroplane, a Cherokee or something like it, rose from the runway and climbed over us.

Narsarsuaq is 100 kilometres inside the Tunulliarfjord, and just 6 kilometres from the Greenland Ice sheet. Narsarsuaq literally means “great plain” though a great many websites are propagating a typo and claiming it means “great plan”. The US built an airbase on this great plain in WW2, which is why a town with a population of just 123 has an international airport.

Breakfast over, we waited.

———

The mist was hanging on the hill,

The sun was still deciding

The PA called our number

And we were on our way

It was a quick, tender (noun, not adjective) ride to the harbour and then about a mile to walk into town. Our midge nets were deployed almost immediately. Lynn and Ameen had not brought their midge nets ashore, relying instead on anti-midge lotion. They were among the many who turned back before reaching the town. Anwari and I pushed on.

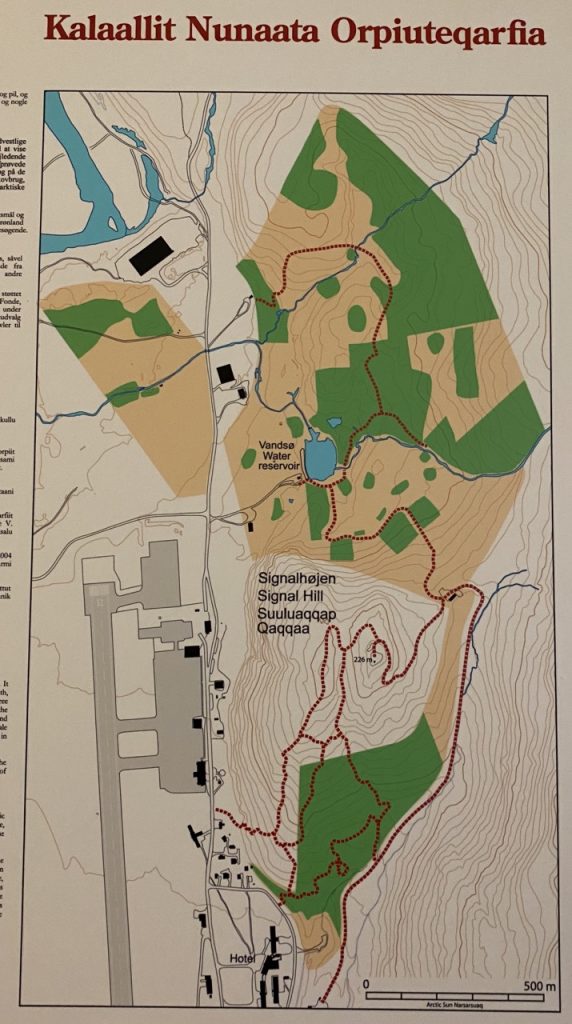

We spotted the gravel track and headed up Signal Hill. Greenland we could see was neither barren, nor lacking in greenery. There were a great many wild flowers and a covering of green scrub. each time we stopped for a breather the views of the fjord had improved. An earlier version of the track looked to have crossed a dilapidated wooden bridge and the whole scene looked like something from a western film. Route descriptions had called our path a gravel track but it was actually made of loose fist-sized rounded rocks, more scree slope than road, so it was a slow and slightly arduous trudge.

At the fist zig in the path reached a flattened shoulder overlooking the valley joining the Kiattuut Sermiat glacier and Tunulliarfik fjord. The glacier, reaching out from Greenland’s ice-sheet, has not reached the fjord in historical times but may have done so within the last 2-3 thousand years. It would then have covered what is now the ‘great plain’ of Narsarsuaq.

This shoulder of the hill must have been a busy area when the US airbase was active. There are the remains of several wooden buildings and a rather brutalist block with metal exhaust hoods. Whatever this was in its heyday, it has been target practice in its retirement.

In the photograph above you might be able to see a couple of women taking a breather in front of the building. Nothing particularly unusual with that, but then one stood up, walked a few paces and began practicing golf swings with her walking pole. As we drew closer I saw she was actually striking a piece of metal embedded in the ground. Intrigued, I called to her that I had thought she was practising golf swings, which got me a harrumph, but no explanation.

The final ascent was actually gravel and we crossed paths with the organised walk-group who were on their way down. We stepped aside as they passed by occasionally flapping their hands at midges. I’m sure I glimpsed a couple of coveting glances at our head coverings. We had only seen one other person in a head-net, a young woman walking a stone’s throw behind us. Don’t worry, I estimated the distance rather than actually lobbing a stone at her. I had been expecting her to overtake us, but she matched our pace and kept her distance. Now I come to think of it, that was a little strange. Perhaps she had us under surveillance – or perhaps she was drawn to a nascent aura of alliteration, feeling forced to follow the fellow fabric-faced wayfarers?

The summit is a modest 226 metres but is well worth the visit. There are good views up the Tunulliarfik fjord and the Kaittuut glacier, with snow topped mountains in the distance and closer at hand, the great plain of Narsarsuaq.

Qassiarsuk across the water from Narsarsuaq is little more than a village now, but was once the centre of a major Norse settlement. At its peak the Norse population would have been about 4,000, but the last written record of the Norse in Greenland is a wedding in 1408.

In 1257, … the devastating volcanic eruption in Indonesia… led to a worsening of the weather condition. Increased ice covers, drifting ice and an increasing number of storms significantly contributed to the hardship of living in Greenland. This contributed to the growing infrequency of trading vessels calling the settlements post-1348. Soon, the upkeep of livestock was abandoned rapidly, while the settlements contracted to the more protected inner zones of the fjords. One of the consequences was a marked shift in diet based on a pastoral economy to one based on seals. Another change may be detected in the density of weaving in the 14th century, when the Norse began to produce warmer and more weather resistant garments.

Medieval Histories

At some point the Norse reached the limit of their will to transform their way of life. Other factors such as the Black Death or conflict with Inuit may may have played their part. In Inuit tradition there are tales that the Norse were attacked and burned in their houses but there is no archaeological evidence of extensive warfare and this may relate to a local conflict.

I walked along a small rocky outcrop to look down on Narsarsuaq and consider the Norse. I then returned to pose for my photo, add a stone to the cairn and nosy about the aerial and hut. These are in good repair and look to be in working order, certainly too new to be the original USAF signal equipment.

While at the top we had noticed a couple walking in the valley between the hill’s two tops. It looked a more interesting route for our return. The couple looked a lot less ‘hill-walky’ than us so if the path proved too troublesome we would no doubt meet them retracing their steps. And as long as we were heading down we would reach either the town or the pebble track.

Once in the valley we were on a path made by footfall, rather than constructed. There were way-markers, red circles on rocks, but we didn’t find them at every fork in the path and there were several forks. When faced with a choice we tried to avoid rejoining the gravel track or turning uphill. Sometimes these choices were rewarded with a red circle on a rock, sometimes a dead end. I presume other walkers had made the same same choices and these wrong turnings were gradually coming to look like tracks.

We passed an obvious (constructed) path leading up to the hill’s lower top and under normal circumstances I would have felt obliged to walk up there. But some effort had gone into dissuading walkers from using that path. There wasn’t a keep out sign but a line of rocks had been placed across that path and arrows pointed along the path we were on. We got the message and passed it by.

The wild-flowers we passed were much the same as I would expect to see in Scotland, with eyebrights, harebells, cats-ear and buttercups in profusion. The heather, though, was never above a hand’s breadth in height and I didn’t immediately recognise the height-challenged willow-herb flowering at knee-height.

On the lower slopes the path passes through the Greenlandic Arboretum, a collection of trees and bushes from arctic and alpine regions. It was set up in 1981 and now covers 200 hectares. South Greenland itself has only three native tree species: the grey willow, downy birch and Greenland rowan, but approximately 110 species have ben established in the arboretum, with almost all sub-artic and sub-alpine trees represented. The trees are significantly smaller than we would see at home, so the forest, though mostly mature trees, has the look of a ten year old forest plantation.

After taking us through the trees the track led us back down to the main road. We were quite close to some ex-airforce buildings which now serve as a museum and cafe. I wandered into the museum not realising there was an entrance fee to pay but the nice lady in the museum shop put me right, politely. I wasn’t alone in my mistake. Better signage might have prevented the same mistake being made by many people. Or perhaps the shop lady just wanted to practice saying “Do you have a ticket?”

It is well worth the 5 krone (about a fiver). The museum has a many interesting photographs and items from when the US airbase was active in the 1940s and 1950s, with some rooms recreated as they would have been back then. Anther section focuses on Greenland’s Norse settlers. And there were stuffed ravens and a model of a DC-6 in SAS livery.

A statue, in Greenland granite, outside the museum shows Erik Thorvaldsson (Erik the Red) on his horse, bending over to lift up his son Leif. His wife Þjódhild is holding the horse.

Erik, though born in Norway moved to Iceland when he was 10 years old. His father had been banished from Norway for manslaughter and his sailed west with his family to live in Hornstrandir. Following in his father’s footsteps, Erik himself was banished after killing Eyjólfr the Foul. Like his father, he too sailed westwards and when his exile was completed he returned to Iceland with stories of the “Greenland” he had explored. He chose a more appealing name than “Iceland” to better entice settlers and it worked. In 985 AD he sailed for Greenland with 25 ships of settlers.

His son, Leif Erikson, would be the first European to set foot in North America. But Leif was not the first European to discover America. That accolade goes to Bjarni Herjólfsson and his crew—they had been blown off course on a voyage from Iceland to Greenland, missed the southern tip of Greenland, and came to an unknown coast. They did not land but returned to Greenland with the news. Leif subsequently bought Bjarni’s ship, hired 35 men and sailed Bjarni’s route in reverse, landing first at a place he called Helluland (possibly Baffin Island), then at several other points along the coast, eventually establishing a settlement at Vinland (in modern-day Newfoundland).

Having consumed the museum (intellectually), we found the first of the treasures required of our quest (fridge magnets). To complete our quest sweets/snacks were needed so we straightened our midge nets (the rain having stopped) and set out in search of the supermarket. This was about the size of a local Spar, but it was well stocked. It even had fresh pomegranates which struck me as slightly strange. Perhaps Danish tourists hanker for them.

Pomegranates were a favourite pattern in silk brocades from the later Middle Ages and the Renaissance. A famous early example is the golden brocade dress of Margaret I, Queen of Denmark, Norway and Sweden (1553 – 1412).

Magnets and sweeties acquired we walked back to the dock. Our ride back to the ship was slightly delayed while the crew manoeuvred a small iceberg out of the way but I was in no hurry. Unfortunately this gave the water seeping along the seat time to reach me. I had an feeling that the seat was growing colder then realised I was sitting in a puddle. So I arrived back on the ship with a wet backside. Despite that, I’ll have to say, it had been a good day out.

Oh, Greenland is a barren place

Traditional (and not true)

It’s a place that bears no green

Where there’s ice and snow, and the whalefishes blow

And the daylight’s seldom seen, brave boys

And the daylight’s seldom seen